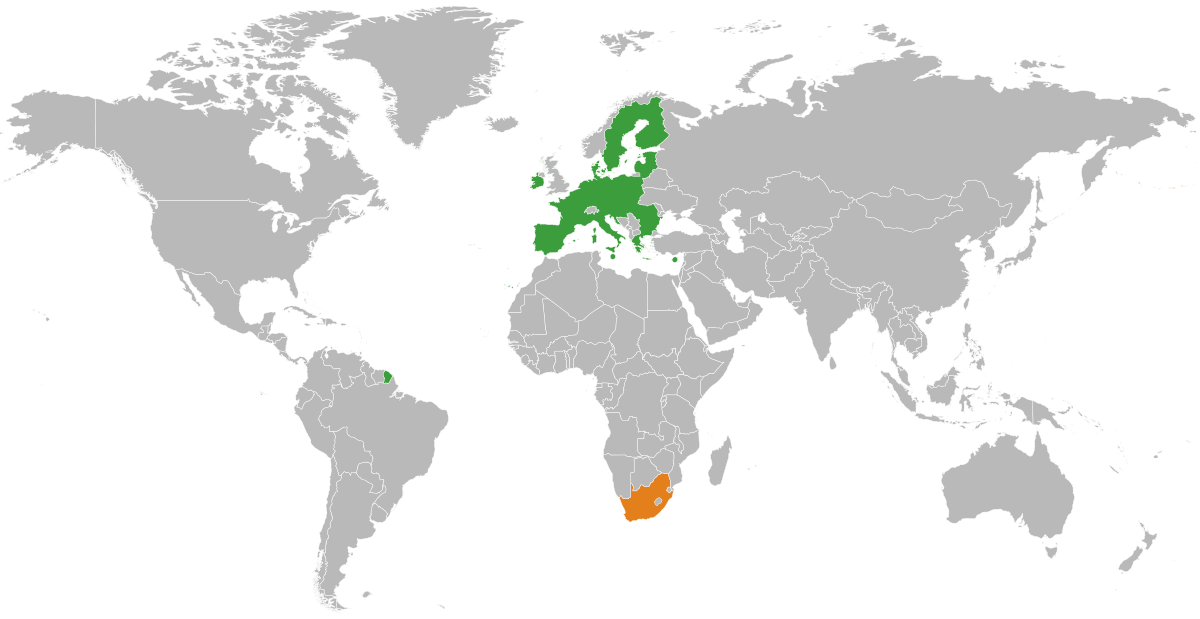

A growing crisis in African agriculture, driven by climate change and biodiversity loss, is jeopardising Europe’s access to essential food imports, including cocoa, coffee, and maize. New research indicates that over half of the European Union’s imports of these staples originate from countries ill-equipped to handle escalating environmental challenges.

A report by UK-based consultancy Foresight Transitions reveals that the EU’s dependence on climate-vulnerable nations for key commodities is intensifying the risk of supply chain disruptions. The study highlights that 96.5% of cocoa, a cornerstone of Europe’s chocolate industry, is sourced from countries with low resilience to climate impacts, while 77% comes from regions suffering significant biodiversity degradation.

West African nations, particularly Ivory Coast and Ghana, are central to this issue. These countries supply the majority of the EU’s cocoa, yet are experiencing declining yields due to erratic weather patterns, deforestation, and soil degradation. Farmers in these regions are increasingly resorting to clearing protected forests to maintain production levels, exacerbating environmental degradation and threatening long-term sustainability.

Coffee production is similarly affected. Ugandan coffee growers report that unpredictable rainfall and rising temperatures are damaging crops, leading to reduced harvests and financial instability for smallholder farmers. The situation is further complicated by the limited availability of climate-resilient coffee varieties and inadequate support for adaptation measures.

Maize, another critical export from Africa to Europe, is facing challenges from prolonged droughts and increased pest infestations. These factors are contributing to lower yields and heightened food insecurity within exporting countries, raising concerns about the reliability of future exports to the EU.

The EU’s own agricultural sector is not immune to climate impacts. Adverse weather conditions have led to an average annual loss of €28 billion, according to a joint report by the European Investment Bank and the European Commission. This domestic vulnerability underscores the importance of stable imports to meet the continent’s food demands.

Experts warn that the current trajectory is unsustainable. Camilla Hyslop, a researcher involved in the Foresight Transitions study, emphasises that these environmental threats are already manifesting in tangible ways, affecting businesses, employment, and consumer prices across Europe.

In response, there is a growing call for the EU to invest in climate adaptation and biodiversity protection initiatives within its supply chain countries. Such efforts could include supporting sustainable farming practices, enhancing infrastructure, and providing financial assistance to smallholder farmers to build resilience against environmental shocks.

The situation also raises ethical considerations regarding the EU’s role in contributing to environmental degradation in its supplier countries. Critics argue that the EU’s demand for commodities like cocoa and coffee is driving deforestation and biodiversity loss in Africa, effectively exporting environmental harm while benefiting from the resources.

Addressing these challenges requires a multifaceted approach that balances the EU’s food security needs with the imperative to support sustainable development in its partner countries. This includes re-evaluating trade policies, investing in climate-resilient agriculture, and fostering equitable partnerships that prioritise environmental stewardship and economic stability.